|

This is my new favourite view in the Highlands, if not the whole of Scotland (but that's a bold claim): Ratagan Pass. My goodness. But these hills were not always here.... The Five Sisters of Kintail hills in these images once were daughters of a local clan chief. There were in fact seven daughters, but amidst a terrible storm one night a ship struggled ashore with two handsome Irish brothers aboard, and they fell in love with the two youngest sisters. Grumbling about this, the older sisters were promised that after returning to Ireland, five more handsome Irish brothers would be despatched back to take their hands and hearts. The sisters watched the loch and waited. They watched and waited by the loch for many years. No ship appeared. The clan chief sought the advice of a bodach, a seer, who told that there were indeed no brothers.

In disbelief, the five sisters visited the bodach themselves. He told of them growing elderly, bitter and haggard if they continued waiting. Instead, he promised that they could stay beautiful, adored and admired. They must go to the head of Loch Duich and wait. And so the five sisters stood at the head of the loch, looking out over the loch. And the bodach turned them to mountains, forever looking out down Loch Duich. They remain admired to this day. I love mountain stories.

0 Comments

I am delighted that Strathspey Storywalks is included in Visit Scotland's brand new Witch Trail Map, for Scotland's Year of Stories.

The map is a good mix of people and places, celebrating a love of nature as an invite for a more thoughtful perspective on what and who a 'witch' is, witchcraft in general, and historical as well as present injustice. My approach on Storywalks is very much to honour the memory of so-called witches by tuning in to the quiet voices within the landscape - we have many stories of 'witches' here in the Cairngorms, and places where they lived, worked and died. Looking at Scotland, there are important things being driven forward at the moment: Witches of Scotland is pushing for a legal pardon for all those accused and killed of witchcraft - follow them to stay up-to-date with the campaign. Due to their work, Nicola Sturgeon gave a formal apology this year on International Women's Day, noting the "egregious historic injustice" to all those accused of witchcraft. Also follow Remembering the Accused Witches of Scotland, who secured an apology from the Church of Scotland for its central role in the persecution in June this year. There remains lots of work to do! In the meantime, download the map of trail locations: Here's July's story for Scotland's Year of Stories - a short one from Orkney, where I was last week, and explains how some of the islands were created...

It's adapted from Tom Muir's story The Caithness Giant in his book of Orkney folk tales, The Mermaid Bride. Apologies for the sound quality, my phone had a funny turn! #YearofStories2022 #YS2022 #Orkney Here's June's story Scotland's Year of Stories. Another favourite and a must-watch for all who live, visit and love the Highlands! Where do midges come from? What ARE midges?!

This is my version of folklorist, musician and storyteller Bob Pegg's brilliant story in his book, Highland Folk Tales. Buy it (or borrow it from the library)! #strathspeystorywalks #yearofstories2022 #applecross #norway Here's a short story for May, for Scotland's Year of Stories. It's one of my favourites from the Isle of Skye, somewhere in the Cuillin mountains...

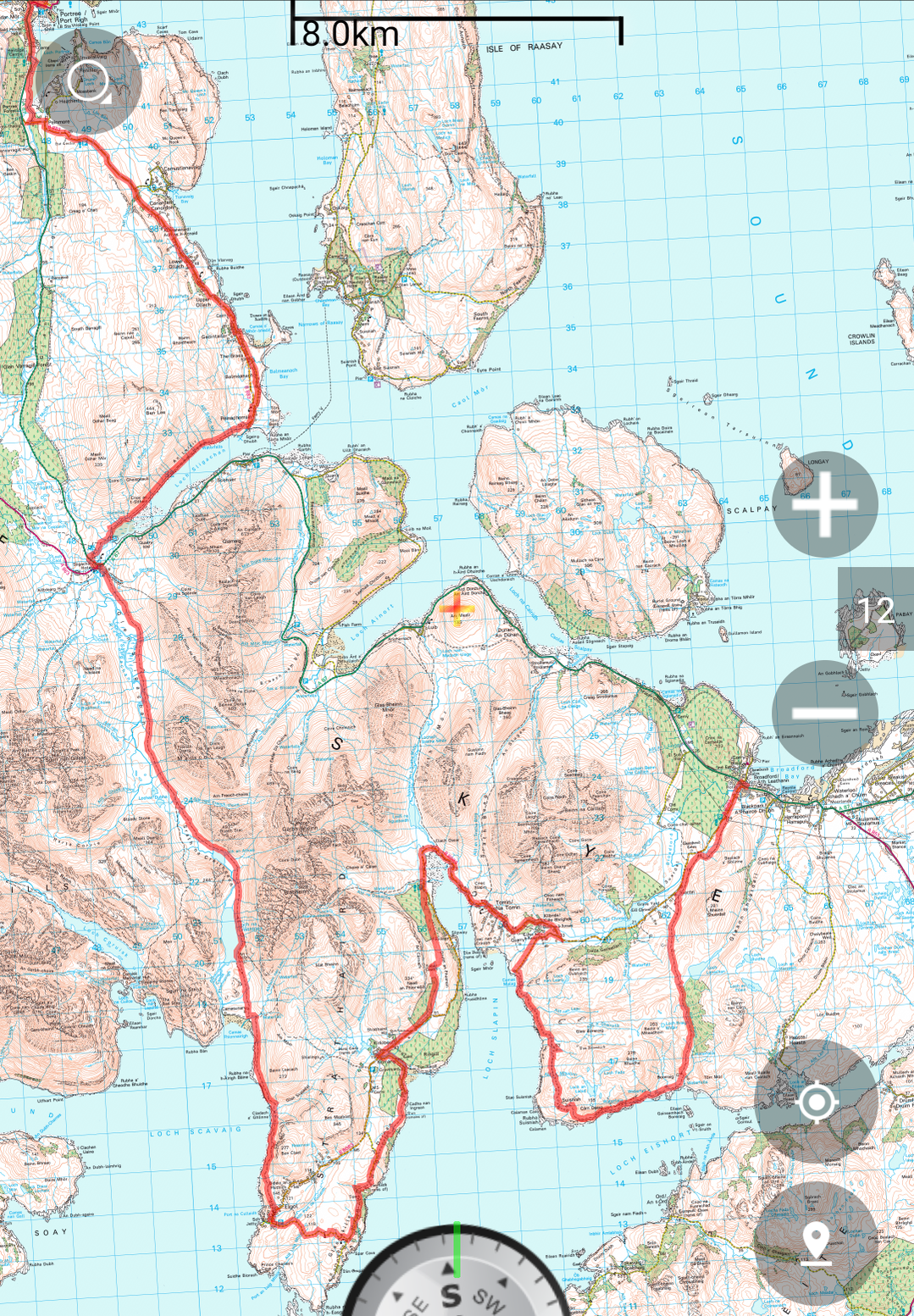

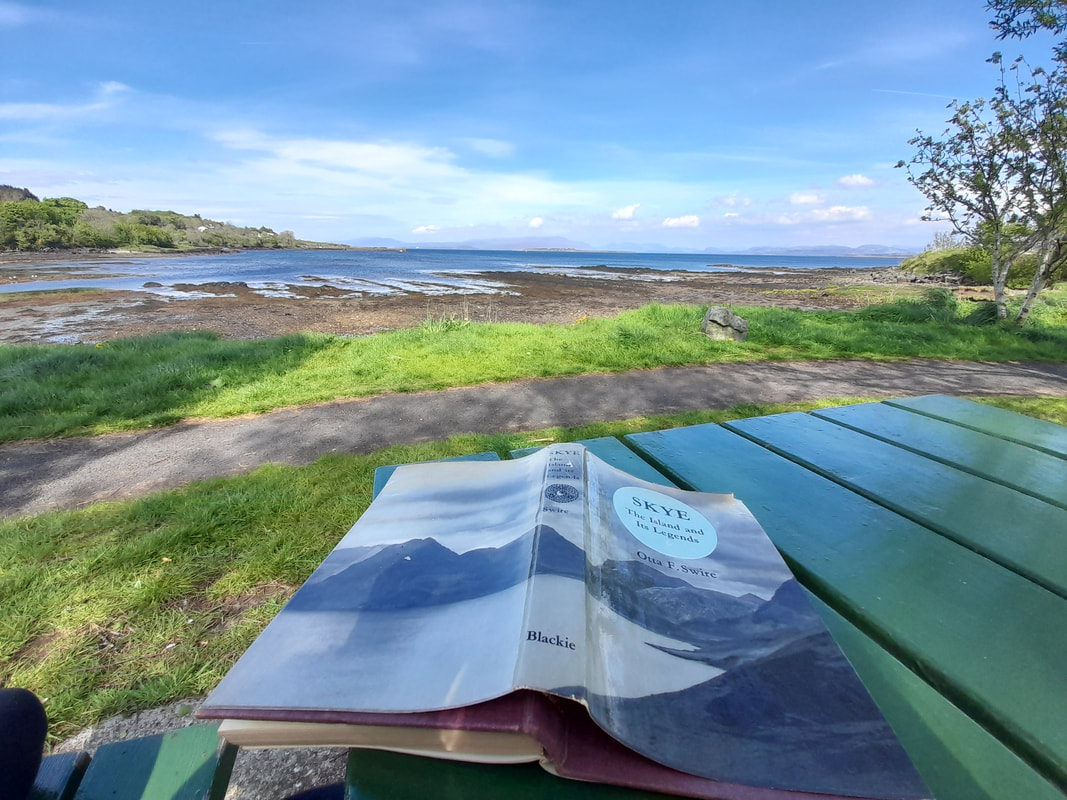

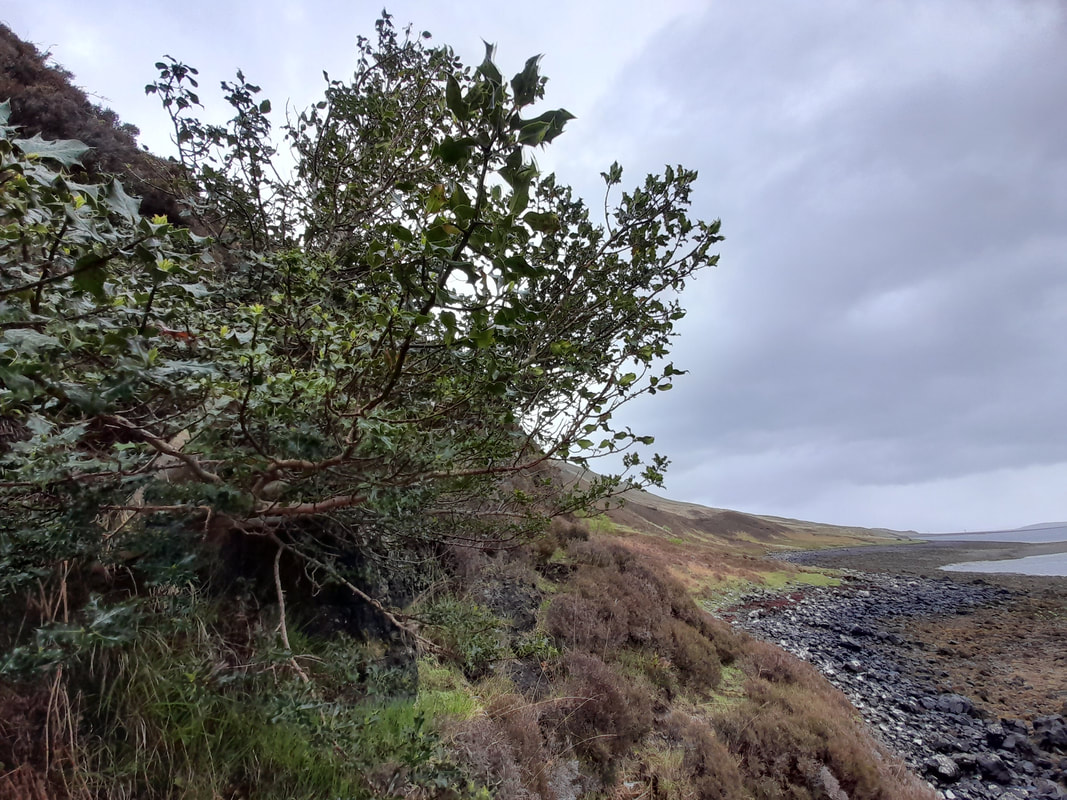

First heard from storyteller Beverley Bryant at the Scottish International Storytelling Festival a few years ago. #strathspeystorywalks #yearofstories2022 #isleofskye #skye Last week I walked part of the Skye Trail to Portree, accompanied by so many stories along the way. The folklore and meanings of places give a totally different perspective on the hills and lochs: they become familiar, places that generations of people have made their own, living and dying there. It means you can never be bored, even if the weather is pretty shocking - especially true in this case - as you're figuring out the land, the story places, and marking meaning as you walk. I had Otta Swire as my guide - and what a wonderful guide she was. She grew up between Skye and Kingussie, and is one of my favourite writers. Here are some of my favourite story snippets from the places I walked through, familiar to many of you no doubt, and will hopefully provide a bit of interest for your next trip to Skye... Broadford petrol station ...is actually a fairy knoll. Fairies may be spotted dancing about this little promontory :) Beinn na Caillich ...towers over Broadford. It's an impressive hill, with a sizeable cairn on the top, easy to spot. The cairn is said to be the grave of a Norse princess, who loved and missed Norway and wanted to be buried looking out to sea in the direction of her homeland. The mountain is named for her - though some say it's named for the cailleach Beira, goddess of winter and creator of Scotland, others for 'Saucy Mary', a Norwegian princess who married a MacKinnon and set up a toll for all the passing ships at Kyleakin. Tigh nan Druinich ...means the house of the craftsmen, and is underground, somewhere near this quarry at Kilbride - hopefully undisturbed! The house is supposed to be round, built of stone, and very small - the people who lived here were equally small, but extremely skilled. Both St Patrick and St Columba employed them to embroider their vestments. Clach Oscar ...is a very short detour from the road at the head of Loch Slapin. The stone was thrown here by Oscar, one of the famous Fianna giants, when he was in good spirits and testing out the weight of stones before he threw (and created) Soay. Loch Sguabaidh ...was the home of a waterhorse or kelpie for many years. This particular kelpie had a liking for pretty girls - and in fact if a girl was taken and escaped, her reputation as a beauty was assured. Some people think this waterhorse was the beast of the Bealach na Beiste, the pass of the monster, not far above the loch, where a Mackinnon of Strath fought and killed a great beast. Burn of Misfortune ...is the English name for Allt na Dunaiche, on the west side of Loch Slapin near the Blà Bheinn carpark. Here, seven girls and a boy made their way up into the hills near the waterfall to spend the summer at the shieling, or summer farm. One evening, the girls went off to a wedding, leaving the young boy alone. To his surprise, in through the door walked seven cats and settled themselves by the fire, all chatting away to each other. They ate all the butter and cream but made it look as if the vessels were still full - and then disappeared into the night. When the girls returned, the boy told the tale, but the girls laughed and disbelieved him, pointing to the full buckets of milk and cream. The next night, the cats returned, and by dawn, all the girls were dead. Their mothers, arriving that day to fetch the milk and cream, cried out in sorrow, 'Airigh mo dunach' - meaning shieling of my misfortune or woe. Kilmarie graveyard ...is a little haven right by the coast, and apparently on the site of a stone circle. The ruins of the old church are also gone, washed away in a huge storm in the 1920s. A sailor had recently been buried in the graveyard and it was said the sea came in to claim him back. There was a strong belief that the sea will search for her souls, so bodies found at sea should always be buried on the water's edge, in case she should flood the land seeking them. The Cuillin Hills How did the Cuillin get their name? There are several theories; here is one. Many moons ago, Sgiath, the mighty warrior goddess, set about establishing a school in the mountains to teach the art of war (in fact Skye might well be named for her - or the other way round - Eilean Sgitheanach). The school became known far and wide, turning out the very finest warriors the world over. News of the school and its female instructor who had never lost a battle, reached the ears of Cuchullin (or Cú Chulainn), the mighty warrior in Ireland. He desired to see this or himself, and took three steps from Ulster to Skye, arriving at Sgiath's school in the mountains. She took no notice of the famous warrior, despite his prowess and the speed with which he learned the martial arts. Frustrated, he challenged every single student to a battle, and won every single one. At which, Sgiath showed a little interest, and gave permission for him to fight her daughter - quite an honour. Cuchullin and Sgiath's daughter fought "for a day and a night and another day" until he defeated her. At which, Sgiath's wrath was swift and mighty. She came down from the mountaintops, and fought Cuchullin for many days and many nights, in the mountains, lochs and sea, but neither gained the upper hand. Sgiath's daughter meanwhile was busy collecting hazelnuts - known for gifting wisdom - to make a stuffing for roast deer. She coaxed them to come and eat. Sgiath thought, "The hazels of knowledge will teach me how to overcome Cuchullin." And Cuchullin thought, "The hazels of knowledge will teach me how to overcome Sgiath. Actually, the hazels of knowledge taught them that neither would overcome the other, so they made peace and promised one another to come to the other's aid should they ever need it. And so, Sgiath presented Cuchullin with a weapon which he would come to be known for - the Firbolg, made by the fairy folk in the mountains - and named these hills after him. The Black Cuillin ...used to be just a wide flat moor, stretching to the sea. Beira held a maiden captive, who she swore would be her prisoner until she washed a brown sheep's fleece until it was white. A rather impossible task! It just so happened that Spring was in love with this maiden, and he wanted her free. He had reasoned with Beira, he had argued with Beira, and he had fought with Beira - but she refused to give her up. Finally Spring turned to his ally the Sun for help (for where would Spring be without the Sun?). The Sun spotted Beira striding across the moor one day, and flung his spear at her. He missed, and Beira cowered under a holly bush for protection, but the fiery spear scorched a blister into the earth, six miles wide and six miles long. For months the earth bubbled and rose, until at least the smoke and the hissing steam cleared to reveal the dark, spiky peaks of the Black Cuillin. Because the mountains were made by the fire of the Sun, the enemy of Beira, the goddess of winter, this is why snow rarely settles on them for long. And what of the maiden? We don't know, but that's how the Black Cuillin came to be! Glamaig At her foot, there was a lodge to which the Fianna warriors would return to after hunting 5,000-6,000 deer in a day. Suidh Fhinn ...overlooks Portree. Finn's seat is where this legendary warrior used to sit and bark orders to drive the deer, all the way over in Strath. We must assume he had a very loud voice, and very good eyesight... Note on stories: all stories are based on Otta's book below, but are written in my words. References Otta Swire (1961) Skye: The Island And Its Legends Geoff Holder (2010) The Guide To Mysterious Skye & Lochalsh https://www.ainmean-aite.scot/ https://www.dwelly.info/ Here's a short story for March, for Scotland's Year of Stories... be careful where you lay your hat if you're in Kinveachy Woods near Boat of Garten!

Adapted from Otta Swire's version in her excellent book 'The Highlands and Their Legends,' published in 1963. #strathspeystorywalks #yearofstories2022 #cairngorms Outlaws, thieves and a president - here's my February story for Scotland's Year of Stories, up Òrd Bàn today in glorious weather!

Featuring Kennapole Hill, the Cats' Den, the Thieves' Road, and Loch Gamhna - all at Rothiemurchus, just south of Aviemore. The main story is from 'Guide to Aviemore & Vicinity,' a treasure trove from 1907 by A McConnachie. This story has unpleasantly familiar 'she asked for it' vibes, symptomatic of the patriarchal society we live in: women must amend their behaviour, dress, etc - or be amended - rather than men amending their behaviour. (Sorry for the wind noise, and suspect Gaelic. It was all unplanned and off the top of my head! Kennapole actually means head of the pool or pit, whoops.) It's Scotland's Year of Stories! Every month I’m going to share one of my favourite stories from the Cairngorms and Badenoch & Strathspey.

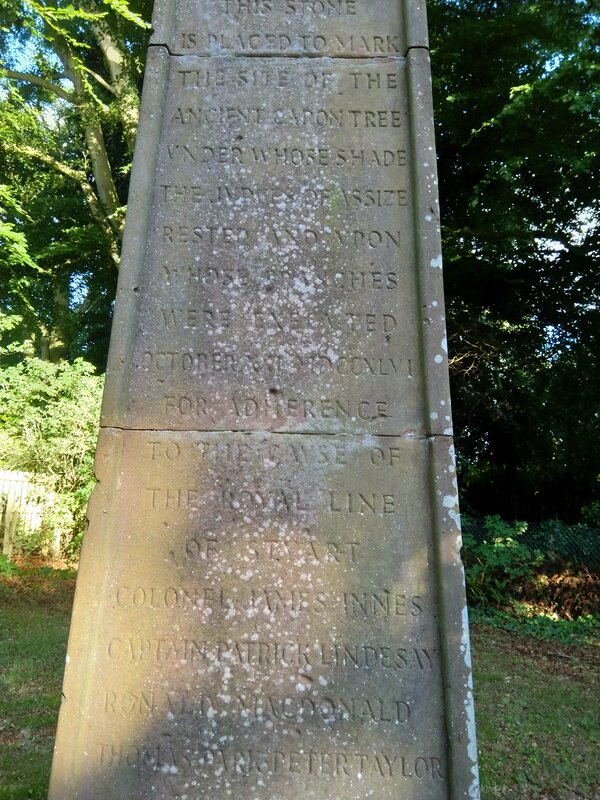

Here's a wintry story for January from Kingussie. It's my version of the story told by Otta Swire in her excellent book, ‘The Highlands and Their Legends’, published in 1963. The wonderful image of Loch Gynack and Creag Dhu is by Kingussie-based photographer and writer David Lintern. He is fond of slow adventure and human powered travel - and he runs workshops and trips on low-impact photography. Have a browse! #yearofstories2022 I might be in northern England just now but I can't seem to escape 'Highland' history! This is the site of the Capon Tree just outside Brampton, near Carlisle. I was curious about the name Capon Tree, did some (online) digging - and bizarrely here unfolds a Jacobite tale! The monument commemorates six men, all members of Sir Charles Edward Stuart's army, captured in various places around Scotland and northern England in 1746 and thrown into the dungeons of Carlisle Castle. They were then "drawn on hurdles up the old highway" to Brampton, up to the Capon Tree, an ancient oak and meeting place, and hung. It was 21 October 1746, less than a year since Bonnie Prince Charlie had been ceremoniously presented with the keys to the city of Carlisle in the centre of Brampton. Three were Highlanders, two were Englishmen, one was Irish. Three were Catholic, three were Protestant. Colonel James Innes of Cullen was nearing 70 and had been a highway surveyor in Banffshire. Captain Patrick Lindesay had been "keeper of the wardrobe" at Holyrood to Bonnie Prince Charlie. The executioner William Stout of Hexham was paid 20 guineas (£2,450 in today's money) for his work that day... ...and there are said to be many spirits and ghouls inhabiting the site of the old Capon Tree, unsurprisingly. References: -- https://yourphotocard.com/Ascanius/documents/The%20Capon%20Tree,%20Brampton,%20and%20its%20Memories.pdf - http://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/currency-converter/ If you'd like to hear more history and folktales of the Cairngorms and the Highlands, join an upcoming short guided walk!

|

AuthorSarah Hobbs - read more on the About page. Archives

July 2023

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed